On the odd occasions I’m in London I always try to fit in a quick hang-around by the banks of the Thames (I’m not even that fussy about which bit). It’s because being anywhere near the Thames estuary always makes me think of Granuaile and the journey she made in 1593 from Clew Bay to Greenwich to seek an audience with Queen Elizabeth I. I suppose the actual voyage itself wouldn’t have been particularly taxing for her: you don’t get to be known as the Pirate Queen of Ireland without being a very able sailor, and Grace O’Malley’s legendary life of pillaging and plundering had taken her much further afield than from the west of Ireland around the south, up the east coast of Britain and down the estuary where the Thames meets the North Sea. But this was no ordinary voyage. This wasn’t business, this was personal.

On the odd occasions I’m in London I always try to fit in a quick hang-around by the banks of the Thames (I’m not even that fussy about which bit). It’s because being anywhere near the Thames estuary always makes me think of Granuaile and the journey she made in 1593 from Clew Bay to Greenwich to seek an audience with Queen Elizabeth I. I suppose the actual voyage itself wouldn’t have been particularly taxing for her: you don’t get to be known as the Pirate Queen of Ireland without being a very able sailor, and Grace O’Malley’s legendary life of pillaging and plundering had taken her much further afield than from the west of Ireland around the south, up the east coast of Britain and down the estuary where the Thames meets the North Sea. But this was no ordinary voyage. This wasn’t business, this was personal.

Continuing the work begun by her dear old dad Henry VIII, Queen Elizabeth’s ever-increasing conquest of Ireland had been encroaching on Grace O’Malley’s power (Granuaile came from a nickname ‘Grainne mhaol’, bald Grace, because it was said she cut off her hair as a child as it would get in the way of the ropes on her father’s ship). Cracks had formed in the once-strong Irish clan system, and it was piecemeal and prone to internal feuding. In Elizabeth’s eyes this made her dangerously open to attack from her enemies on the continent. Frustrated and impatient with what he saw as Granuaile’s dismissive and insubordinate attitude, the English governor of Connacht, Sir Richard Bingham murdered Granuaile’s eldest son and seized another of her sons as well as her half-brother, Donal-na-Piopa. He confiscated her cattle and horses and installed his own soldiers in her home, Rockfleet Castle on Clew Bay (pictured). You can understand why Granuaile was hopping mad and decided to sail to England to petition Elizabeth I for their release. But as a known leader who could quickly command hundreds of loyal followers should she choose to do so, the decision to travel to the Queen’s court was a dangerous one. Bingham and his cronies were out for her blood too, not just that of her family. Of course not only was this before the shipping forecast but it was long, long before sea areas and what we would recognise as navigational aids. This was a time when pirates were routinely hung inside iron cages along the banks of the Thames, their rotting bodies left to the mercy of the seagulls. (A forecast of a sort, I suppose, as was this signature of Elizabeth on the death warrant of Mary Queen of Scots in 1587. Elizabeth’s seal is below her signature.)

It is remarkable that two of the most powerful people in that patriarchial and sexist society were women. Unfortunately, it would still be remarkable now. Elizabeth I famously sent Granuaile a list of 18 questions about her life, her work (you can be sure the term ‘piracy’ wasn’t used by either of them), and the laws of Irish society. According to Elizabeth’s advisor, Granuaile had ’overstepped the role of womanhood’, which seems to me to be a dangerous criticism to make in the company of such a trail-blazing Queen of England. However, Elizabeth must have decided to let that one pass, and despite her advisors’ fury, the Queen agreed to grant her visitor an audience. Anne Chambers refers to the encounter in her book Granuaile, as ‘When The Sea Queen Met The Virgin Queen’.

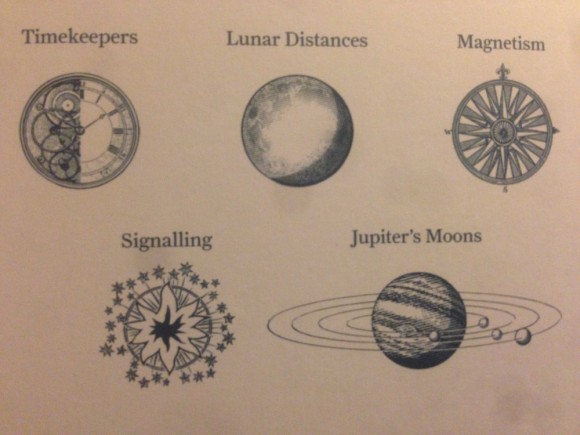

They met in the summer of 1593 at Elizabeth’s palace at Greenwich. (Greenwich is also where the first Board of Longitude was set up in 1714, primarily as a result of the watery fate of Sir Cloudesley Shovell and his crew, which I wrote about in this post about sea areas Sole, Lundy and Fastnet.) Granuaile’s journey to the court at Greenwich must have been so different from all others she had previously undertaken because it was about saving a life; about giving not taking. The circumstances of their meeting and what happened during it inspired my short story The Dead Of Winter which was published in the Irish Independent on May 31st in the Hennessy New Irish Writing competition. Co-incidentally that was the same day I was first on the Marian Finucane radio show to talk about the Maeve Binchy Travel Award, which seems like an particularly appropriate connection between these sea areas of the Shipping Forecast and The General Synopsis At Midnight. The following is my version of what happened when Grace met Elizabeth…

The Dead Of Winter

Typical, just typical. I’ve trudged five cold, rain-sodden miles out from Newport to visit Grace O’Malley’s castle only there’s nothing to see. Not even a sign – unless you count the tatty Office of Public Works: Keep Out notice swinging from the broken railings, which I don’t. What was I expecting to find, I wonder? A boom-time Interpretative Centre? Jaunty, pirate-themed cafe? I jam my hands harder into the pockets of my fleece. Even a leaflet would have been nice. Rockfleet Castle sits at the edge of the water, squat and square and solid. It must be black as soot on the inside. Now that I’m closer (that gap in the railings somewhat undermining the creaking authority of the Keep Out notice) I can see that the castle is the edge of the water: its walls climb from the sea, a gift thrown to the land.

castle only there’s nothing to see. Not even a sign – unless you count the tatty Office of Public Works: Keep Out notice swinging from the broken railings, which I don’t. What was I expecting to find, I wonder? A boom-time Interpretative Centre? Jaunty, pirate-themed cafe? I jam my hands harder into the pockets of my fleece. Even a leaflet would have been nice. Rockfleet Castle sits at the edge of the water, squat and square and solid. It must be black as soot on the inside. Now that I’m closer (that gap in the railings somewhat undermining the creaking authority of the Keep Out notice) I can see that the castle is the edge of the water: its walls climb from the sea, a gift thrown to the land.

I have taken myself away from my life for three days.’That’s all I want,’ I told my husband, ‘three days away.’

‘A mini-break?’ he said. ‘There’s great deals, hotels are on their knees this time of year. But I’m too busy to take time off.’ He was sitting on the end of our bed, clipping his toenails. ‘Maybe… ‘ he said, ‘if Mam took Cuan, and Jack went to your sister? I’ll think about it.’ Each slim sliver he placed neatly on the floor, and when he was finished he gathered them into a pile. A tiny white shoal dropped into the bin under his night table. For me to fish out, I supposed.

‘By myself,’ I said.

‘You want a mini-break by yourself?’ He looked puzzled. I realised he could imagine only the holiday we would take together. Us, sipping Guinness in country pubs; us frittering away a day in deciding where to have dinner. He thought I wanted the holiday I would have with him, only without him.

‘I want to be alone. For three days. That’s all. I won’t get through the winter otherwise.’

‘But what about the boys?’ he said, in bed now, the glow of the iPad ghoulish on his face. He thinks I make too much of it. Of her. That it – she – consumes me. That I alone tighten the iron band around my heart. I know he thinks it, and he knows I know.

Water laps the sides of the castle, licking the stone.

‘You alright there?’

‘Jesus!’ I jump, whirl around, ‘You scared me half to death!’

‘Sorry.’ The man is wearing an oil slicker and black bobble hat. He steps back and holds up his hands as though I am cranky dog, liable to nip. He looks older than me, though that could be the beard. He points down a half-hidden slope that leads to a small jetty. The prow of a boat bobs in and out of sight. ‘You were getting fierce close to the edge.’

‘I was looking for a door.’

‘It’s around the far side, but the castle’s shut up for the winter. You’ve no fear of ghosts then? It’s haunted by Grace O’Malley herself.’

‘Yeah,’ I say, ‘Sure.’

He nods and I can’t tell whether he didn’t get that I was being sarcastic, or just didn’t care.

‘She died here, but her head was buried out on Clare Island and her body is said to set sail from here every night in search of it.’

‘There’s no such thing as ghosts.’

‘There’d be no such thing as ghost stories, so,’ he shrugs. ‘I’ll take you out in the boat, if you want? I’m done fishing, there’s feck all out there today but it’s light enough for a half hour.’

‘You’re a fisherman?’ I say stupidly. I’ve never met a fisherman before, which now strikes me as odd, considering how much fish I eat.

‘Yeah,’ he says, ‘But in the summer I do better from the tourists. Two hour tour, 20 euro a head. Seals, mussel farms, Louis Walsh’s summer house, the lot.’ When he nods the bobble on his hat jigs up and down. ‘They can’t get enough of Louis Walsh.’

I imagine my husband’s look of horror if he could see me now: alone in the dusk in a dead-end with this stranger, this sea-faring giant. My jeans are stiff from the rain and it’s awkward to climb down the metal ladder to the boat so I take off my thick gloves. I gasp when my hands touch the freezing iron and he – Murrough, his name is – grabs my elbow. Once again I picture my husband’s face (waves of horror, a distinct undertow of reproach) and all of a sudden I’m conscious of the scared thump in my heart and about to exclaim, no! do you know what? I think I’ll leave it for today after all, when he jumps back saying, ‘It’s them last few rungs are the tricky ones, people jump thinking they’re in, only they’re not.’

We chug out into Clew Bay, the engine announcing us to the darkening sea. I guess I can always fling myself overboard if I have to, though the water looks so unforgiving I decide I will take my chances on board. I feel an unexpected pang for the Seaview Hotel, for my small room with its commanding view of the leisure centre’s external ventilation system. Guilt had caused me to book cheaply and unwisely, and thanks to its Winter Warmer Offer – three nights for the price of two, breakfast and dinner thrown in – the hotel is humming with guests. My fellow bargain hunters are either much older than me and enjoying mid-week leisure time, or families with pre-schoolers.

‘I took the early retirement package,’ a man had confided to me in the lift, his pinkish cheeks and juniper breath telling a story of golf, of gin and tonics at the nineteenth. ‘And we’ve not looked back since.’

I am that holiday oddity; a woman alone. In the restaurant I’ve noticed older women looking curiously at me. The mothers of small children regard me with something more like envy: I know they are picturing my long hours of unbroken sleep in clean sheets, and my not driving around aimlessly for an hour every lunchtime because the toddler refuses to nap in the twenty-euro-per-night-surcharge travel cot.

I have spent the last two days rambling up and down The Greenway trail before coming back to the hotel for a late swim when the pool is quiet. I have kept myself busy and alone. That way I can think about Poppy, can let her fill my thoughts entirely, and still play fair – more than fair; play kind – with the present. When I phoned home Cuan and Jack were chatty and said they missed me. My husband sounded tense and bemused and only when I hung up did I realise why: he hadn’t actually believed I’d go.

‘Who owns that house there?’ I point at the long low lines of grey stone; a ghostly shape flittering through a bank of winter trees.

‘Yer man who used be the American Ambassador. Funny enough, no-one gives a feck to see his house.’ The boat motors along for another minute and then, ‘Once upon a time,’ Murrough says.

‘What?’ This must be his patter for tourists. ‘A fairy story?’

‘A true story.’

‘Then you shouldn’t have once upon a time. If your story is true, it’s a legend and they can’t start with once upon a time.’ I am aware of how daft, how childishly pedantic, I sound.

‘It’s my story,’ he doesn’t look at me, ‘I can have it whatever way I want.’

I turn my head to the sea because my eyes have filled with tears.

‘Once upon a time,’ he says, then laughs, ‘Fair enough. In 1593, Grace O’Malley, pirate queen of Ireland, set sail for London from the very same harbour as ourselves. Her youngest son Tibóid – her favourite for reason of being born at sea – had been taken prisoner by the English and charged with treason, which carried a sentence of death.’

He pauses. I edge closer to the wheelhouse.

‘She sailed her ship the Malendroke as if her own life depended on it and when she got to the Thames Estuary word was sent to Queen Elizabeth. Pirate corpses hung along the Estuary, so she’d have known her fate if she didn’t play her cards right. Elizabeth sent her a list of eighteen questions, but when she received Granuaile’s answers she left her waiting six weeks before agreeing to see her.’ His voice is bigger than the story needs, I suppose he’s used to a chattering, camera-flashing audience. ‘It felt like a lifetime to Granuaile, but it was a good omen; she’d been warned she might be still waiting at Christmas.’

Christmas. Poppy died on December twenty-second, three years ago.

‘She had meningitis,’ I’ve heard my husband tell people, but to me meningitis had her. It consumed her, destroyed her. And now, when summer is over and the boys go back to school, I feel the draw into winter as a tug to that date.

I close my eyes and let four hundred years fall away. Two women living men’s lives face each other. A Queen trussed up in a farthingale, face harshly painted, rotting teeth shored up with pieces of stale bread. Bright and garish, she is a flightless tropical bird. Grace O’Malley has hair woven from waterweeds and loose, homespun clothes. Her face is raw from a life at sea. They are the two most powerful women of their age and the only time they will ever meet is for one to beg the other for a life.

The boat lurches and seawater slops over my jeans. Spray touches my eyelids and they shoot open. Through the wet light of the wheelhouse his yellow oil slicker gleams like gold.

‘-and so,’ he is saying and I realise I must have missed a bit, ‘Granuaile’s words worked. Elizabeth released her son and let her ply her trade in peace in these waters. The Queen was so impressed she had her lads draw a map of Ireland with Granuaile included as a chieftain of Mayo. She was the only woman ever to be named a chieftain.’ He pauses and raises his eyebrows till they disappear under his hat. ‘And,’ he adds with a grin, ‘they all lived happily ever after.’

‘How do you know so much about her?’

‘My own people are descended – I don’t know how many greats back – from her grand-nephew, he was another Tibóid.’ He turns the wheel in a wide arc. ‘Let’s head in now, maybe we’ll get a seal or two to perform for us on the way.’

We head back for the harbour and Newport and the road to Dublin and my life of the last three years and the years before that and the years yet to come. I can’t see it, but I know Croagh Patrick rises, tall and broad and severe, from the mists on the land to one side. I turn my back to it and look at Rockfleet looming ahead, the moon turning its grey stone to silver. The castle was owned by Granuaile’s second husband, Murrough says, but under Brehon Law she divorced him by calling Richard Burke, I dismiss you, from a window and lo! it became hers. ”Twas easier done in them days,’ he grins.

I picture her on the turret, red hair fizzing and gossamer-thin nets spinning from her fingers as far as her eye could see and her heart could want.

He tucks his boat into the crook of the harbour and we clunk up the ladder. My lungs are full of sea-cold air, my throat scratchy with salt. I offer him twenty euro. ‘Ah, you’re grand,’ he gently pushes my hand away, ‘You didn’t see much after all.’

And from up ahead I hear the wind grab the loose Keep Out notice and beat it, beat it hard against the railings.

Want to sea more?

Granuaile lives on, and I don’t mean through such things as the ill-fated musical The Pirate Queen. She is at sea still: the Commissioners of Irish Lights boat the ILV Granuaile is one of the most advanced vessels of its kind. (It’s also available to hire, should you and your wallet be inclined). In 1997 I spent a day on board its predecessor, the Granuaile II, in the company of the CIL and an artist called Stefan Gec, who had a made a specially constructed, fully operational navigational buoy from steel cast from eight decommissioned Soviet submarines.

There is a Granuaile Visitor Centre in Louisburgh, Mayo. Contact granuailelouisburgh@hotmail.com for details.

There are no likenesses of Grace O’Malley in existence apart from that in the photograph used at the start of this post. The alabaster statue (photo by Joseph Mischyshyn) is a version of the bronze statue that is located outside along the road to Westport House near the north end of the bridge over the Carrowbeg River. Westport House was built in the C16th by – and is still owned by – descendants of Granuaile.

In chapter one of Finnegans Wake, James Joyce uses the story of Granuaile (‘her grace o’malice’) and her kidnapping of the grandson of the Earl of Howth. Apparently the Earl refused to receive her in his castle because he was having his dinner. Fair enough, some would say. Furious at such treatment, she kidnapped his grandson and returned him only when the Earl promised to lay an extra place at this dinner table for evermore.

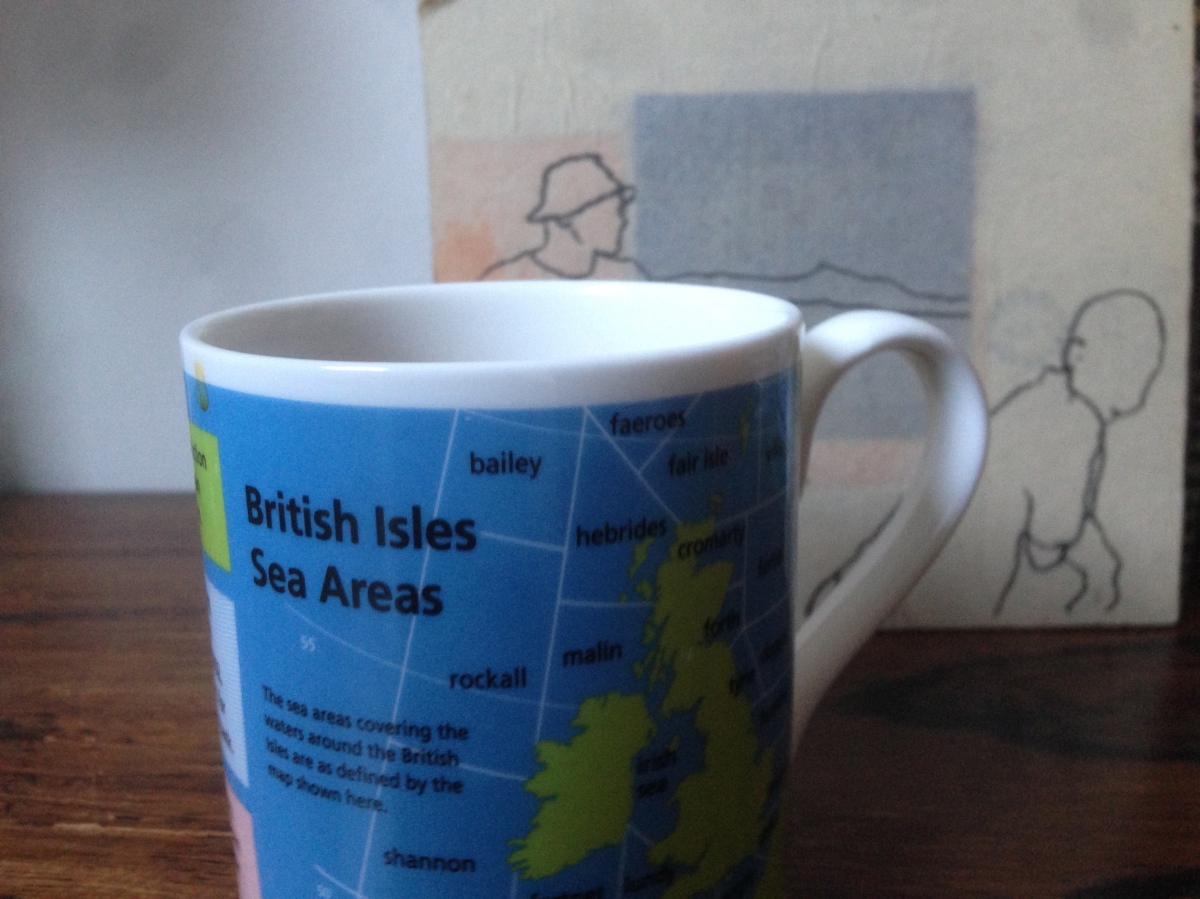

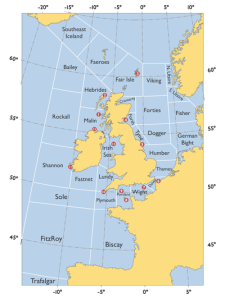

The General Synopsis At Midnight is my exploration of the sea areas of the BBC R4 Shipping Forecast, thanks to the Maeve Binchy Travel Award. The earlier post ‘Counting Down To Midnight’ explains the project.

And look, here we are. I think the chap standing between us is a pickpocket. Since then, I visited the 31 Sea Areas of the Shipping Forecast by land, water and air and – in the case of those I explored through their folklore or history – by making things up. And now, six months later, it’s time to put the map away and listen to Sailing By, the music by Ronald Binge that accompanies the 0048 broadcast. (Have a listen, but be warned: it’s hypnotic.) If you’re new to this project, then the easiest thing is to back to the beginning and work your way forward. It’s a blog, not Serial – I know, right? as Sarah Koenig might say, like, right? – it doesn’t really matter if you read them in the wrong order, but it would make more sense to start here, Counting Down To Midnight.

And look, here we are. I think the chap standing between us is a pickpocket. Since then, I visited the 31 Sea Areas of the Shipping Forecast by land, water and air and – in the case of those I explored through their folklore or history – by making things up. And now, six months later, it’s time to put the map away and listen to Sailing By, the music by Ronald Binge that accompanies the 0048 broadcast. (Have a listen, but be warned: it’s hypnotic.) If you’re new to this project, then the easiest thing is to back to the beginning and work your way forward. It’s a blog, not Serial – I know, right? as Sarah Koenig might say, like, right? – it doesn’t really matter if you read them in the wrong order, but it would make more sense to start here, Counting Down To Midnight.

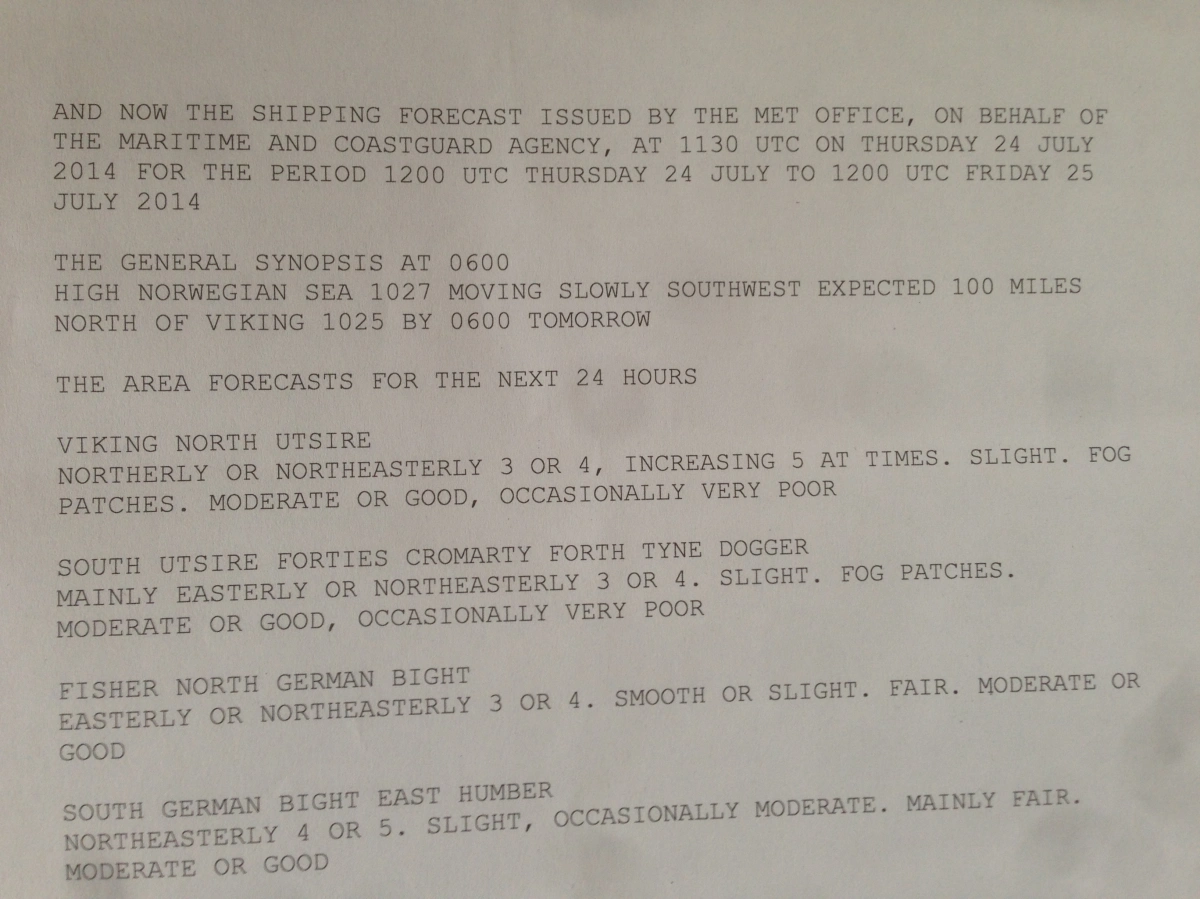

(And there I am, in the aforementioned interval). Now, it’s not that I was expecting Captains Birds Eye, Pugwash and Hook to be in the front row or anything, but I did look around the audience and assume that like me, they were all armchair enthusiasts; people who love the Forecast for its poetry, but don’t depend on it for their livelihood or welfare. Since I began this project, many people have asked me who still uses the Shipping Forecast these days? Who needs it, now that all the information you could possibly want is available online? It was one of the first questions I had for Craig Snell when I pulled up a chair at his desk last July. The BBC too has been asking this question: last year it sent out a questionnaire to members of the Royal Yachting Association, the national governing body for boating, enquiring how they get their information about the weather when they’re at sea. If the answer had come back ‘duh, the internet,’ would that have meant the death knell for the Forecast and its nighttime companion music? Radio 4 controller Denis Nowlan said the survey showed – phew! – the Forecast on Radio 4 longwave continues to be a primary or secondary source of marine safety information. An informal survey the BBC Feedback programme held at the Cornish fishing port Newlyn revealed that, although younger fishermen are less likely to use it as their go-to source, it’s because the longwave broadcast isn’t at the mercy of digital signals and technology that it’s still relied upon.

(And there I am, in the aforementioned interval). Now, it’s not that I was expecting Captains Birds Eye, Pugwash and Hook to be in the front row or anything, but I did look around the audience and assume that like me, they were all armchair enthusiasts; people who love the Forecast for its poetry, but don’t depend on it for their livelihood or welfare. Since I began this project, many people have asked me who still uses the Shipping Forecast these days? Who needs it, now that all the information you could possibly want is available online? It was one of the first questions I had for Craig Snell when I pulled up a chair at his desk last July. The BBC too has been asking this question: last year it sent out a questionnaire to members of the Royal Yachting Association, the national governing body for boating, enquiring how they get their information about the weather when they’re at sea. If the answer had come back ‘duh, the internet,’ would that have meant the death knell for the Forecast and its nighttime companion music? Radio 4 controller Denis Nowlan said the survey showed – phew! – the Forecast on Radio 4 longwave continues to be a primary or secondary source of marine safety information. An informal survey the BBC Feedback programme held at the Cornish fishing port Newlyn revealed that, although younger fishermen are less likely to use it as their go-to source, it’s because the longwave broadcast isn’t at the mercy of digital signals and technology that it’s still relied upon. Though my explorings and wanderings are over, in another way the project is beginning, because now I have the fun of playing with all this fact and trying to turn it into fiction. I’m ending The General Synopsis at Midnight by listening to today’s lunchtime broadcast. Showers are expected later today in my nearest area, Irish Sea, in case you’re wondering. Did Craig Snell write this one? Thanks to the Maeve Binchy Travel Award I am able to picture him sitting at his desk in front of a bank of screens, painstakingly making the world at sea safer and more knowable for the rest of us. At the words Northeast Fitzroy, Sole I’m back on St Agnes on the isles of Scilly chatting to a stranger about why a man would choose to be buried standing up; with Faeroes, Southeast Iceland I’m on a boat in the ninth century determined to find a land that supposedly doesn’t exist; with Lundy, Fastnet I’m staring up at the black tower of Ballycotton lighthouse…

Though my explorings and wanderings are over, in another way the project is beginning, because now I have the fun of playing with all this fact and trying to turn it into fiction. I’m ending The General Synopsis at Midnight by listening to today’s lunchtime broadcast. Showers are expected later today in my nearest area, Irish Sea, in case you’re wondering. Did Craig Snell write this one? Thanks to the Maeve Binchy Travel Award I am able to picture him sitting at his desk in front of a bank of screens, painstakingly making the world at sea safer and more knowable for the rest of us. At the words Northeast Fitzroy, Sole I’m back on St Agnes on the isles of Scilly chatting to a stranger about why a man would choose to be buried standing up; with Faeroes, Southeast Iceland I’m on a boat in the ninth century determined to find a land that supposedly doesn’t exist; with Lundy, Fastnet I’m staring up at the black tower of Ballycotton lighthouse…

t that? Good, because I’m already astronomically out of my depth. Maskelyne too was sent to Barbados (I picture him and William sweating in their powdered wigs, glowering at each other from the shade of opposing palm trees.) Harrison’s machine was more accurate, but Maskelyne’s system was cheaper. Maskelyne was appointed the Astronomer Royal in 1765, which meant he was one of the assessors of the prize as well as an entrant. Hmmm. One of his main jobs at the Royal Observatory (also in Greenwich) was making observations at night, and to ward off the cold he designed an ‘observing suit’, complete with padded feet like a baby’s sleep suit, to wear under his overcoat (that’s the top half of it in the photo). It’s on display in the National Maritime Museum and, as the information panel so delicately phrases it, ‘seems to have been well used.’ Pretty exciting thought isn’t it: this garment may be first known appearance of the Onesie.

t that? Good, because I’m already astronomically out of my depth. Maskelyne too was sent to Barbados (I picture him and William sweating in their powdered wigs, glowering at each other from the shade of opposing palm trees.) Harrison’s machine was more accurate, but Maskelyne’s system was cheaper. Maskelyne was appointed the Astronomer Royal in 1765, which meant he was one of the assessors of the prize as well as an entrant. Hmmm. One of his main jobs at the Royal Observatory (also in Greenwich) was making observations at night, and to ward off the cold he designed an ‘observing suit’, complete with padded feet like a baby’s sleep suit, to wear under his overcoat (that’s the top half of it in the photo). It’s on display in the National Maritime Museum and, as the information panel so delicately phrases it, ‘seems to have been well used.’ Pretty exciting thought isn’t it: this garment may be first known appearance of the Onesie.